15th MARCH 2019

You can’t come to Cambodia and not visit Angkor Wat. Well, obviously you can, but it would be a bit like visiting Cairo without seeing the pyramids. The vast, ancient temple is such a symbol of Cambodia that it even appears on the national flag. I’m excited to be making this side trip, although my day begins in rather unpromising fashion.

My stomach had felt a bit rumbly during the night, but I didn’t think anything of it until I go for my morning poo. The first one slips out very satisfyingly, before the second effort comes shooting out like a raging waterfall, spraying brown liquid splatter everywhere. What the Fuck ? How did that happen ? I sit there, dribbling, then go to wipe my arse. The act of doing so causes yet more brown mess to come shooting out all over my wiping hand. Jesus, this is gross. I wash my hands more carefully and thoroughly than I ever have before. I’m at a bit of a loss as to why I’ve got the shits, because yesterday I only had breakfast at Vanny’s and my two meals at No. 72 Restaurant. My best guess, based purely on timing, is that chicken from the restaurant is the most likely culprit. If only I’d stopped after the first meal !

I’m feeling so woozy that I toy with the idea of delaying my trip, but I’ve already booked my bus and accommodation. I traipse downstairs and pick lethargically at my breakfast, before heading back up to my room to lie under the fan for a while. The cooling air and some deep breathing makes me feel slightly better, and I decide to go ahead with the journey. Vanny orders me a tuk-tuk, driven by one of his mates, who weaves through busy traffic to get me to the bus station in plenty of time.

I find the bus and choose a seat, only to be told I have to sit in Seat 13 like it says on my ticket. A Cambodian guy in his forties sits down beside me with a Seat 14 ticket, even though the rear of the bus is empty. We get talking and I find that he’s a tuk-tuk driver based in Siem Reap and (of course) he offers me a tour. He also shows me a picture of himself alongside Angelina Jolie, from when she was filming Tomb Raider in the temples around Siem Reap. This chap was actually an extra in the film, playing the role of a Khmer Rouge soldier.

Leaving Phnom Penh becomes a painfully slow crawl through traffic, taking us a full hour to escape from the city. I’m not feeling great by this point either; the combination of a dodgy stomach and the motion of a hot coach has me feeling like I’m either going to throw up or shit myself. How the Hell am I going to get through a six hour bus journey feeling like this ? I’m nauseous, sweating like a pig and about one minute from getting up to be physically sick. Then, almost like a minor miracle, air vents above me start cooling the sweat on my forehead, which in turn makes me feel a whole lot better. I doze fitfully, until the bus stops for a rest break and I take this opportunity to go and lie on the vacant rear seat. When the bus resumes it’s journey, I remain crashed out on the back seat. There are a few more waves of nausea to deal with, but they’re a lot easier to handle when lying down. At some points I get really hot, at others really cold and my muscles are feeling a bit achy. My immediate panicky thought is that I might have contracted malaria, as you can’t help being bitten by mosquitos at some point. The muscle stiffness seems to pass though, and we carry on rolling slowly towards Siem Reap. From my prone position I notice rain on the bus window, and I manage to sit up for the final twenty minutes into town. This is the first rain I’ve seen in almost two months.

My accommodation, The Cashew Nut Guesthouse, is about two minutes walk from the bus station, which is an absolute godsend in my current condition. I check in, have a hot water and lemon to soothe my guts and book myself on two single day tours of the temples. I go upstairs, lie under air-conditioning and basically don’t move from that position all evening. By 10.00pm I’m beginning to feel far healthier, so hopefully a good night’s sleep will see me right for tomorrow’s temple tour.

The next morning I wake with settled bowels, feeling infinitely better than I did yesterday. A simple breakfast of baguette, scrambled egg and fruit salad sets me up for the morning and I go outside to meet Seth, who will be my tuk-tuk driver for the next two days. At our first stop I have to buy a ticket, emblazoned with my photo, which will gain me entry into all the temples over the weekend. I think the photo may well be used as an identification check, but it will also stop me from selling the ticket on when I’m finished.

Then we drive off to see temple after temple, some Hindu, some Buddhist, some Khmer. They all formed part of the ancient capital city of Angkor, and most of the structures have been dated back to almost one thousand years ago. I spend ages in the first temple, marvelling at the intricate designs and awed by just how long the building has stood here. Then, an uphill walk in thirty-five degree heat gets me to the second, while Seth (Sett) remains with his tuk-tuk. From up here I see jungle stretching out for miles below, and also catch a glimpse of the huge Angkor Wat temple in the distance, hidden tantalisingly amongst the trees.

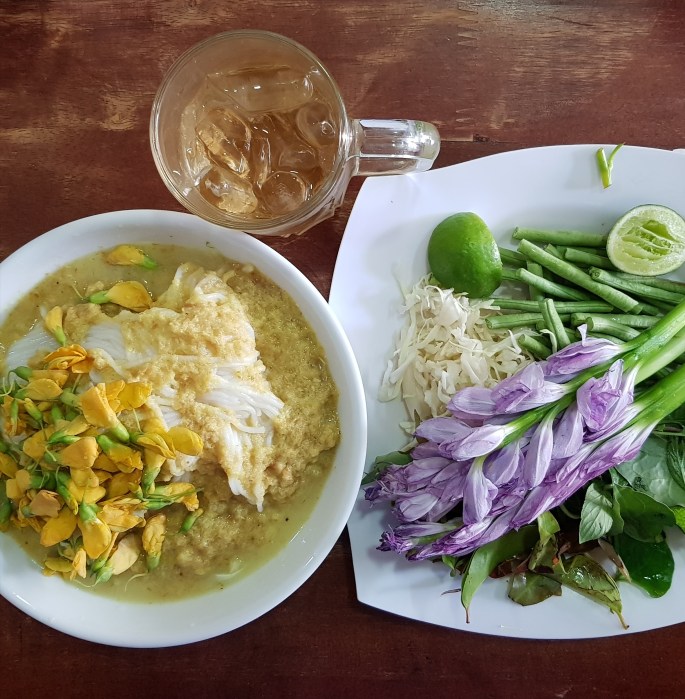

When we stop to eat I find out that Seth expects lunch bought for him as part of the deal. He has a fish curry soup, whilst my stomach issues lead me to choosing the plainest, bland option of boiled spring rolls. I don’t really mind buying his lunch, even though the touristy food prices here are double that of Phnom Penh. Afterwards we head off to another temple ruin, situated on the far side of a giant wetlands. As I walk through on a raised pathway, I pass fishermen and boys standing waist deep in water and half a dozen grazing water buffalo. The final stop is a tall temple where you can climb up to watch sunset, although having three hundred other tourists at the top spoils the moment somewhat. The entire upper level is crammed with people taking selfies and trying to pose for photos that make it look like they’re ‘holding’ the setting sun. I really can’t be arsed with them, even though I’m a tourist myself. I better get used to it though, because tomorrow I’m off to see sunrise at Angkor Wat, Cambodia’s premier tourist attraction.

On the Sunday I’m up at 4.30am, collect my packed lunch from the guesthouse fridge and meet Seth outside for a tuk-tuk ride in the dark. We drive along Siem Reap’s famous ‘Pub Street,’ which still has food stalls trading through from Saturday night, as well as new ones setting up for this morning. Half an hour later we park close to the Angkor Wat site, and I follow the crowds, torches and lights that are marching towards the temple. I sit on a wall overlooking a rectangular moat that surrounds the complex, whilst a stream of flashlight-carrying tourists cross a pontoon in front of me to enter the temple grounds. Through the gloom I can just about make out the shadowy outline of Angkor Wat, the distinctive towers a slightly darker colour than the surrounding sky. Gradually it starts to get lighter, but there’s no spectacular sunrise with a band of cloud on the horizon. The sky colour simply moves from black, to grey and then into daylight.

The normal, fixed walkway over the moat is under repair, so I squeak my way across to the temple on a temporary plastic pontoon. I knew a lot of folk had crossed this way in the darkness, but I had no idea just how many until I see them all inside. There are thousands. Nearly everyone makes for the main temple like a flock of sheep, so instead I walk round the grassy outside of the grounds to try and get some sunlit photos from the rear vantage. Most of the stones used to build Angkor temples are really dull and dark, so this direct sunlight makes for a much better photo.

Then I climb up to join the hordes inside the huge main temple. It’s a spectacular spot, three levels high and supposedly one of the largest religious monuments in the world. What makes Angkor Wat so distinctive are the five enormous towers, four in each corner and one in the middle, set out like the Number Five pattern on a dice. The towers are shaped almost like tall acorns, adorned with ‘petals’ to make them look like lotus flower buds. Inside there’s a queue and a thirty minute wait to get to the highest level, so I forgo that to explore the terraces, galleries and storylines carved intricately into the stone walls. Most of my time is spent wondering how these wonders could have been constructed nearly a thousand years previously. My tolerance for tourist crowds isn’t great, so after a few more pictures I call it quits and return to meet Seth.

We carry on to Bayon Temple, which has more stone-carved storylines of battles and myths, dozens of huge, smiling Buddha faces on columns and about two hundred Chinese tourists. Then it’s the very cool Ta Phrom Temple, which was used as one of the locations when parts of Tomb Raider were filmed here. This temple is unique, as a lack of restoration and human interference has allowed it to remain in almost the same condition as when it was discovered. The surrounding jungle has encroached and taken over, with massive silk-cotton trees and strangler figs growing straight through the roofs of some buildings. Enormous gnarled tree roots twist and crawl over the ruins below, appearing to strangle them like giant, woody constrictor snakes. Visually, the place is astonishing, but the scrum of tourists queuing for pictures makes it hard work.

We head off for lunch, with me treating Seth again and opting for a mild fish curry served in a coconut. Over food, he tells me that Cambodia was actually bombed far more than Vietnam during the ‘Vietnam’ War. He and his friends would find mortar shells and grenades as kids, with one friend losing a finger after playing with a grenade that exploded. He then tells me his older brother was once kidnapped by the Khmer Rouge and forced to train with them, before escaping and making his way back home. I’m not sure whether to believe him, but then I reason that most stories from the Khmer Rouge era seem scarcely believable nowadays.

There are a couple of more temple stops on the way back, although I’m getting a bit templed-out by now. They all seem to pale in comparison after seeing Angkor Wat and Ta Phrom. On our return we stop alongside the moat that surrounds Angkor Wat, where Seth gives me a few more interesting snippets of information. I’m told that the moat used to contain crocodiles as a defence measure, and that if it ever dries up there’s a chance the Angkor Wat temple may collapse one day. Apparently the temple site is built on sandy ground that is kept damp by underground water wells. Now, with Siem Reap continually growing and attracting more tourists, there are many more new hotels and businesses that require access to water. All these new consumers then drill bores to tap into this underground water source. It’s ironic that the town has grown so much because of Angkor Wat, yet catering for all these tourists may end up damaging this crown-jewel of temples.

It’s roasting by mid-afternoon back at the guesthouse, so I have a swim and relax by the backyard pool. It never occurred to me until today that this swimming pool is probably using underground water that helps support Angkor Wat. I should feel slightly guilty, but I guess that Siem Reap wants to keep getting busier and busier as Cambodia becomes more accessible to mass tourism. I’m glad I got to see Angkor Wat now, before the town becomes even more stupidly crowded than it already is. It’s one of those places that would have been great to visit twenty years ago, just after Cambodia opened up to the world again. In the late nineties only 7,500 hardy travellers would come to Angkor Wat. Today that number has grown to over two million visitors each year. That’s a crazy transformation. It’s been a good few days though, despite the tourists, and great to see another ‘bucket list’ destination. Tomorrow it’s back to Phnom Penh and back on my bike.